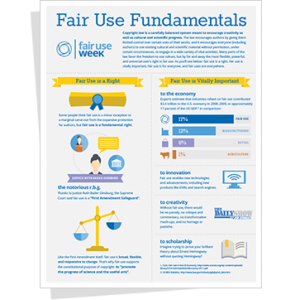

Fair Use & Permissions

What is Fair Use?

Fair Use is an exception in the law to excuse what might otherwise be infringing activity. There are specific types of use to be considered fair, and these types fit with the educational activities that take place at ECU: criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, research and scholarship. There are also four factors to consider whether a particular use is fair. All four factors must be weighed for every use.

How does the law describe Fair Use? Here is section 107, from http://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap1.html#107:

§ 107 . Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use40

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

The Four Factors

Much of the content from this section is from University of Minnesota Libraries, thanks to their Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License.

Each possible use of an existing work must be looked at in detail and the law spells out several factors that determine whether a use is fair. No one factor is decisive – you always have to consider ALL of them, and some additional questions. Even after considering all relevant issues, the result is usually in impression that a particular use is “likely to be fair” or “not likely to be fair.” There are rarely definitive answers outside of courts.

1. Purpose and Character of the Use

This is the only factor that deals with the proposed use – the other three factors deal with the work being used, the source work. Purposes that favor fair use include education, scholarship, research, and news reporting, as well as criticism and commentary more generally. Non-profit purposes also favor fair use (especially when coupled with one of the other favored purposes.) Commercial or for-profit purposes weigh against fair use.

Transformative uses are normally viewed as fair uses. Here are a couple of questions that indicate transformativeness:

- Has the material you have taken from the original work been transformed by adding new expression or meaning?

- Was value added to the original by creating new information, new aesthetics, new insights, and understandings?

Stanford University supplied the questions above, and supplies a couple of examples, including parody. See http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/fair-use/four-factors/.

2. Nature of the Original Work

One element of this factor is whether the work is published or not. It is less likely to be fair to use elements of an unpublished work – which makes sense, basically: making someone else’s work public when they chose not to is not very fair, even in the schoolyard sense. Nevertheless, it is possible for use of unpublished materials to be legally fair, depending on the totality of the four factor evaluation.

Another element of this factor is whether the work is more “factual” or more “creative”: borrowing from a factual work is more likely to be fair than borrowing from a creative work. This is related to the fact that copyright does not protect facts and data. With some types of works, this factor is relatively easy to assess: a textbook is usually more factual than a novel. For other works, it can be quite confusing: is a documentary film “factual”, or “creative” – or both?

Uses from factual sources are more likely to be fair than uses from creative ones – though not every source is easily classified!

3. Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used

Using proportionately smaller amounts is usually more likely to be fair as long as what you use is not only the “heart” of the work used.

Amount: this is an element that some guidelines give bad advice about. A use is usually more in favor of fair use if it uses a smaller amount of the source work, and usually more likely to weigh against fair use if it uses a larger amount. But the amount is proportional! So a quote of 250 words from a 300-word poem might be less fair than a quote of 250 words from a many-thousand-word article. Because the other factors also all come into play, sometimes you can legitimately use almost all (or even all) of a source work, and still be making a fair use. But less is always more likely to be fair.

Substantiality: this element asks, fundamentally, whether you are using something from the “heart” of the work (less fair), or whether what you are borrowing is more peripheral (and more fair). It’s fairly easily understood in some contexts: borrowing the melodic “hook” of a song is borrowing the “heart” – even if it’s a small part of the song. In many contexts, however, it can be much less clear.

Borrowings from the heart of a work are usually less likely to be fair than borrowings of peripheral elements.

4. Effect of the Use on the Potential Market For or Value Of the Source Work

This factor is truly challenging – it asks users to become amateur economists, analyzing existing and potential future markets for a work, and predicting the effect a proposed use will have on those markets. But it can be thought of more simply: is the use in question substituting for a sale the source’s owner would otherwise make, either to the person making the proposed use or to others? Generally speaking, where markets exist or are actually developing, courts tend to favor them quite a bit. Nevertheless, it is possible for a use to be fair even when it causes market harm.

Isn’t Citing the Source Enough?

NO! Citing sources to avoid plagiarism is an important activity, but plagiarism and copyright infringement are two separate types of misconduct. Citing your source will not protect you from claims of copyright infringement.

Would a disclaimer protect you? No again. A disclaimer is “a statement that ‘disassociates’ your work from the work that you have borrowed” for instance, by saying that your work is not “associated with or endorsed by” the copyright holder of the original work. See more at http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/fair-use/four-factors/.

Getting Permission

If your use would not be covered by Fair Use or other exemption, then you should either select an alternative source or get permission to use what you need.

Permission requests should be written and include the following information: your name and contact details, the date of request, a complete citation to what you want to use, and a specific description of how you want to use the work. This specific description should include how long you will need to use the work, and for what audience(s). Also include a means of response for the rights holder, and KEEP the response! If the rights holder does not respond, choose another work. The rights holder might respond with certain conditions, for instance a fee you must pay to use the work. If you cannot comply with the conditions, do not use the work. ECU’s University Copyright Officer can help ECU personnel with permissions letters, or you can view samples at Columbia University’s site: http://copyright.columbia.edu/copyright/permissions/requesting-permission/model-forms/.

Permissions for Music, Images, or Films: these are often mediated by one or more organizations. See the University of Texas’s Permissions page or Perdue University’s links for getting permissions from a variety of organizations based on material type, for instance Music, Motion Pictures, and Images.

Additional Sources on Fair Use:

- Columbia University: Fair Use in Education and Research

- Stanford University: Copyright and Fair Use

- University of Minnesota Libraries: Using Copyrightable Materials

- University of Texas Libraries: Copyright Crash Course, Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials

- Center for Media and Social Impact: Fair Use

- See especially the Codes of Best Practice for Journalism, Video, Poetry, Images, and others